While the alphabet hasn’t changed in more than 100 years, ideas on teaching literacy certainly have. To ensure students benefit from the use of evidence-based reading instruction, The Elisabeth Morrow School’s curriculum aligns with the Science of Reading, a multifaceted approach based on decades of research that continues to evolve as educators learn more, eschewing trends to build a solid foundation of reading for our students.

The Reading League, an organization whose mission is to advance the awareness, understanding, and use of evidence-aligned reading instruction, describes the Science of Reading as a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research — conducted over the last five decades across the world and derived from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages — about reading and issues related to reading and writing. “The Science of Reading has culminated in a preponderance of evidence to inform how proficient reading and writing develop; why some have difficulty; and how we can most effectively assess and teach and, therefore, improve student outcomes through prevention of and intervention for reading difficulties.”

“For a long time, the teaching of reading was centered around balanced literacy or the cueing system, which is telling a child that they can figure out a word by looking at a picture or by looking at the first letter and taking a guess,” says Little School Learning Specialist Jenn Dare. “Now we know that’s not how children learn to read. But that was, and still is, a practice in a lot of schools, unfortunately.”

What are the building blocks of reading? According to the National Reading Panel’s 2000 report, five essential components form the foundation of any successful reading instruction program:

- Phonemic awareness: Understanding spoken language is made up of individual sounds

- Phonics: Matching sounds (phonemes) in spoken language to print (graphemes/letters)

- Fluency: Reading text accurately with proper pronunciations

- Vocabulary: Understanding and using words in conversations

- Comprehension: Independently understanding what is read

EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTION

Two theoretical reading frameworks, part of the Science of Reading that The Elisabeth Morrow School uses, include Gough and Tunmer’s Simple View of Reading (1986) and Hollis Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001).

The Simple View of Reading theory explains that a student’s reading comprehension is based on their ability to recognize words (through decoding and then automatically) and comprehend language (the meaning behind the words).

Scarborough’s Reading Rope encompasses the complexity of learning to read and consists of various strands. Background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge make up the language comprehensive stands, while phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition make up the word recognition strands. When all these strands intertwine, it results in reading comprehension.

“In early education at Chilton House, serving children aged 2 through kindergarten, phonemic awareness and vocabulary teaching are naturally integrated into many of the children’s explorations, projects, and activities,” Dare says. “Songs, nursery rhymes, and poetry offer joyful and meaningful opportunities to identify and manipulate speech sounds.” For instance, in the “Apples and Bananas” song, each stanza substitutes a new vowel sound in parts of the words apples, bananas, and eat. “That’s phonemic awareness,” says Dare.

“But a common misconception about the Science of Reading is that it’s just about phonics and phonemic awareness. With our youngest students, we devote a great deal of instructional time to word recognition,” says Dare. “When children develop automaticity with word recognition, such as accurately detecting syllables within a word, fluently blending sounds to decode an unfamiliar word, or reading many words instantly, their cognitive load is lightened. Students can devote focus, attention, and cognitive energy to comprehend a text. If you have ever learned another language, you might have experienced the feeling of working so carefully to sound out and read every word accurately, only to realize that you have no idea what you just read and have to reread it.”

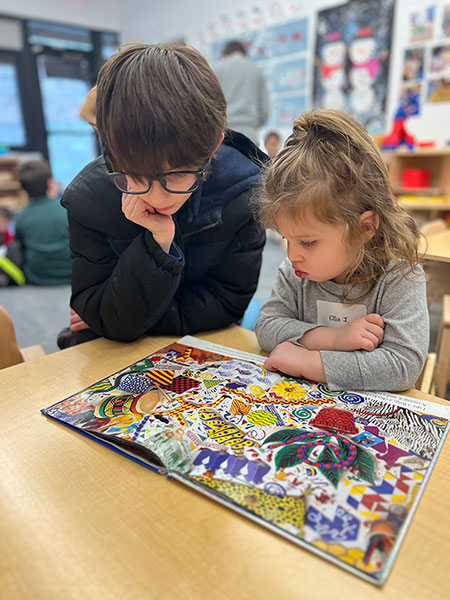

Our young readers at EMS are developing language comprehension through their many experiences in and out of school. Listening to stories read by teachers and family members, watching informational videos, and engaging in lively and rich conversations about books or other topics of interest support children in building and strengthening their background knowledge, vocabulary, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge.

“A kindergarten student may not be able to read a National Geographic book about dolphins conventionally, but they will begin to notice important features of nonfiction texts, such as captions, glossaries, and photographs, while collecting interesting and sophisticated words, such as mammal, bottlenose, dorsal, and aquatic as their grown-up reads — and rereads — the text,” says Dare.

Our instructional focus shifts primarily to language comprehension by third and fourth grade.

This is the significant shift from learning to read to reading to learn. With mastery of the code, our third and fourth graders, as well as our students in middle school, read independently to build background knowledge, actively determine the meaning of new words using the context, and decompose writing in various genres to analyze the specific text features, grammatical structures, and academic vocabulary to inform and enhance their own written pieces. Teaching prefixes, suffixes, and Latin and Greek roots help older students strengthen both language comprehension and word recognition as they encounter more complex vocabulary in our various disciplines.

“In the 2024–2025 academic year, we are introducing new programs aligned with the Science of Reading, further strengthening our students’ developmentally appropriate progression from Chilton House through Morrow House,” says Head of School Marek Beck, Ph.D. “To start with, an upgraded reading and language arts curriculum in kindergarten will yield even higher levels of proficiencies as our students become successful readers, exceptional writers, and effective communicators.”

Reading aloud at home is one of the best ways to boost children’s development, says Dare, suggesting families make learning fun by playing games like “I Spy” when out for a walk or adapting it on trips to the grocery store. Parents can ask their children to find something that starts with a particular sound and then let them try to figure it out as they go up the aisle.

“Little things like that give young students the focus to listen to sounds, and when they have that strong foundation, then they’re able to connect those skills to when they’re exposed to the print later in kindergarten and make those explicit connections between the sounds they hear and the letters that represent those sounds,” Dare says.

ASSOCIATING SOUNDS

One key difference between the Science of Reading and other methods is the reliance on memorization. In the Science of Reading, students are instead learning to “crack the code.” Segmenting sounds to write the letter (or letters) that spell those sounds is considered encoding, while blending the sounds represented by the letter (or letters) to read the word is decoding.

Children may associate sounds with particular letters, especially the letters within their names, even before kindergarten. In kindergarten, students begin their formal instruction in learning the relationship between the sounds in spoken language and the letters that represent those sounds. They also learn to write letters and words, which helps them access “sound pictures” when visualizing and writing uppercase and lowercase letters.

“It’s important to integrate writing, spelling, and reading to ensure that children learn that the code works in both directions,” says Dare.

Our youngest learners become acclimated to the consistent activities and routines embedded in the curriculum, including sound warm-ups, dictations, and word talks. There are no surprises or distractions when introducing new information so students can focus solely on the new concept. These activities and routines are woven into the next level of reading instruction, allowing students to continue cracking and mastering the code in our lower school.

WORD DETECTIVES

Understanding the Science of Reading has significantly changed Dare’s approach to teaching “sight words” — words that appear frequently in reading and writing that students can instantly recognize.

“It was assumed that children could only learn these types of words by recognizing their shape or memorizing them because they couldn’t be sounded out or didn’t follow the rules,” she says. “We know now that many of these words are completely decodable.”

For example, “said” is an example of a tricky sight word. Dare will start her lesson by saying the word and using it in a sentence. Then, our students segment it, count the sounds, and map them to the spellings. They’ll write “s” on the first sound line, “ai” on the second, and “d” on the third. “At that point, the students are eagerly telling me, ‘I can’t believe two vowels spell one sound,’ or ‘I thought there would be an E there!’” she says.

The reading group then discusses the irregular part of the word, before Dare covers the word to have them write it from memory. She encourages them to say the sounds as they write the letter or letters. Then, they generate sentences orally. “This allows every student to connect the meaning of the word to the sounds and spellings we just studied,” Dare adds. “They love being word detectives and talking about the unusual parts in words and often make connections to new words.”

For a student with a dyslexic profile, it takes more exposure, practice, and slowing down the content “to make sure they are making the connections between the pronunciation of the word, to the sounds of the word, the spelling, and the meaning,” she says. “But all of the research shows that kids with dyslexia do learn how to read.”

Once students have become proficient in decoding, teachers focus on deepening comprehension. “Teachers consistently observe and assess students throughout the year to gather information about a student’s strengths and areas where they need growth or support,” says newly appointed Assistant Head of Lower School Natasha Pronga. “In fourth grade, specifically, teachers use this information to group students so they can tailor instruction to meet each child’s needs. These groups are flexible and change regularly based on students’ demonstrated behaviors. This approach allows us to challenge students who are ready with concepts, such as identifying themes, synthesizing information, and understanding cause and effect. Meanwhile, other readers and groups may focus on skills like identifying the main idea and making inferences.”

The Science of Reading is not like a “finished thing,” says Dare. “There’s always research, and there’s always things to investigate. It’s important to look at the research and incorporate it into practice or change some practice to help kids gain access to the code.”

There's No Better Time to Support Your Child's Education

Every time you donate to one of Elisabeth Morrow's dedicated funds, you help enrich the daily experiences of our community on campus. STEAM spaces are enhanced, library catalogs are expanded, scholarships are funded, and teachers are hired. Every day, you can see the impact your generous donations have on campus.